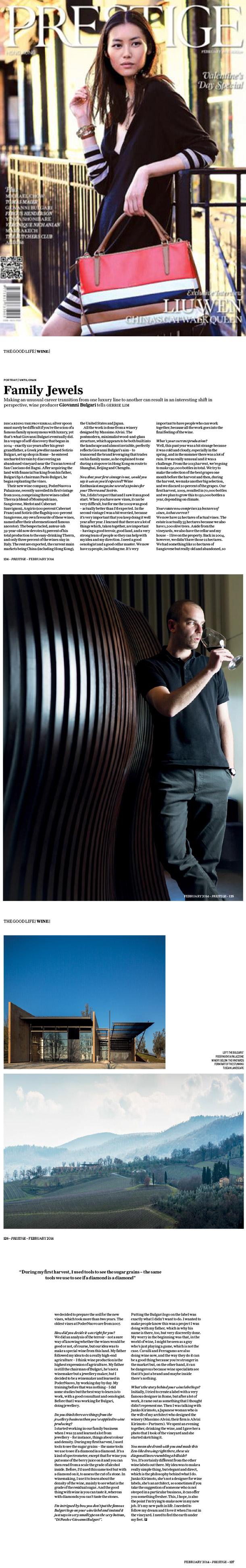

Family Jewels

Making an unusual career transition from one luxury line to another can result in an interesting shift in perspective, wine producer Giovanni Bulgari tells Gerrie Lim

FAMILY JEWELS

MAKING AN UNUSUAL CAREER TRANSITION FROM ONE LUXURY LINE TO ANOTHER CAN RESULT IN AN INTERESTING SHIFT IN PERSPECTIVE, WINE PRODUCER GIOVANNI BULGARI TELLS GERRIE LIM

Discarding the proverbial silver spoon must surely be difficult if you’re the scion of a famous family synonymous with luxury, yet that’s what Giovanni Bulgari eventually did. In a voyage of self-discovery that began in 2004 – exactly 120 years after his great- grandfather, a Greek jeweller named Sotirio Bulgari, set up shop in Rome – he entered uncharted terrain by discovering an abandoned vineyard near the Tuscan town of San Casciano dei Bagni. After acquiring the land with financial backing from his father, Bulgari SpA chairman Paolo Bulgari, he began replanting the vines.

Their new wine company, PoderNuovo a Palazzone, recently unveiled its first vintage from 2009, comprising three wines called Therra (a blend of Montepulciano, Sangiovese, Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon), Argirio (100 percent Cabernet Franc) and Sotirio (the flagship 100-percent Sangiovese, my own favourite of these wines, named after their aforementioned famous ancestor). The bespectacled, auteur-ish 39-year-old now devotes 85 percent of his total production to the easy-drinking Therra, and only three percent of the wines stay in Italy. The rest are exported, the current main markets being China (including Hong Kong), the United States and Japan.

All the work is done from a winery designed by Massimo Alvisi. The postmodern, minimalist wood-and-glass structure, which appears to be both built into the landscape and almost invisible, perfectly reflects Giovanni Bulgari’s aim – to transcend the brand leveraging that trades on his family name, as he explained to me during a stopover in Hong Kong en route to Shanghai, Beijing and Chengdu.

Now that your first vintage is out, would you say it was as you’d expected? Wine Enthusiast magazine scored 92 points for your Therra and Sotirio.

Yes, I didn’t expect that and I saw it as a good start. When you have new vines, it can be very difficult, but for me the 2009 was good – actually better than I’d expected. In the second vintage I was a bit worried, because it’s very important that you keep doing it well year after year. I learned that there are a lot of things which, taken together, are important – having a good terroir, good land, and a very strong team of people so they can help with my idea and my direction. I need a good oenologist and a good cellar master. We now have 19 people, including me. It’s very important to have people who can work together, because all the work goes into the final feeling of the wine.

What’s your current production?

Well, this past year was a bit strange because it was cold and cloudy, especially in the spring, and in the summer there was a lot of rain. It was really unusual and it was a challenge. From the 2013 harvest, we’re going to make 130,000 bottles in total. We try to make the selection of the best grapes one month before the harvest and then, during the harvest, we make another big selection, and we discard 20 percent of the grapes. Our first harvest, 2009, resulted in 70,000 bottles and we plan to grow this to 150,000 bottles a year, depending on climate.

Your estate now comprises 22 hectares of vines, is that correct?

We now have 22 hectares of actual vines. The estate is actually 55 hectares because we also have 1,200 olive trees. Aside from the vineyards, we also have the cellar and my house – I live on the property. Back in 2004, however, we didn’t have those 22 hectares. We had something like 10 hectares of Sangiovese but really old and abandoned, so we decided to prepare the soil for the new vines, which took more than two years. The oldest vines at PoderNuovo are from 2007.

How did you decide it was right for you?

We did an analysis of the terroir – not a sure way of knowing whether the wines would be good or not, of course, but our idea was to make a special wine from this land. My father followed my idea to do a really high-end agriculture – I think wine production is the highest expression of agriculture. My father is still the chairman of Bulgari, he’s not a winemaker but a jewellery maker, but I decided to be a winemaker and learned in PoderNuovo, by working day by day. My training before that was nothing – I did some studies but the best way to learn is to work, with a good consultant and oenologist. Before that I was working for Bulgari, doing jewellery.

Do you think there are things from the jewellery business than you’ve applied to wine producing?

I started working in our family business when I was 22 and learned a lot from jewellery – for instance, things about colour and density. During my first harvest, I used tools to see the sugar grains – the same tools we use to see if a diamond is a diamond. It’s a kind of spectrometer, except that for wine you put some of the berry juice on it and you can then read from a scale the grade of alcohol inside. Before, I’d used this same tool but with a diamond on it, to assess the cut of a stone. In winemaking, I use it to learn about the density of the wine, mainly to see what is the grade of the residual sugar. And the good thing with wine is you can taste it, whereas with diamonds you can’t taste the stones.

I’m intrigued by how you don’t put the famous Bulgari logo on your wine label and instead it just says in very small type on the very bottom, “Di Paolo e Giovanni Bulgari”.

Putting the Bulgari logo on the label was exactly what I didn’t want to do. I wanted to make people know this was a project I was doing with my father, which is why his name is there, too, but very discreetly done. My worry in the beginning was that, in the world of wine, I might be seen as a guy who’s just playing a game, which is not the case. Cavalli and Ferragamo are also doing wine now, and the way they do it can be a good thing because you’re stronger in the market but, on the other hand, it can be dangerous because wine specialists see that it’s just a brand and maybe inside there’s nothing.

What’s the story behind your wine label logo?

Initially, I tried to create a label with a very famous designer in Rome, but after a lot of work, it came out as something that I thought didn’t represent me. Then I was talking with Junko Kirimoto, a Japanese woman who is the wife of my architect who designed the winery (Massimo Alvisi; their firm is Alvisi Kirimoto + Partners ). We spent an evening together, drinking the wine, and I gave her a photo that I took of the vineyard and she started sketching it.

You mean she drank with you and made this Zen-like drawing right there, these six diagonal lines resembling a hillside?

Yes. It’s certainly different from the other wine labels out there. My idea was to make a really simple thing, but elegant and direct, which is the philosophy behind what I do. Junko Kirimoto, she’s not a designer for wine labels, she’s an architect, so sometimes if you take the suggestion of someone who is not steeped in a particular business, it can offer you something fresher. This, I hope, is also the point I’m trying to make now in my new job. It’s my new path in life. I needed to follow my dream and I love it when I’m out in the vineyard. I need to feel the earth under my feet.